His Life

Born on November 23, 1892, in Saint Petersburg fashion and costume designer Romaine de Tirtoff, also know as Erté (which is the French pronunciation of his initials, R.T.), was one of the most prodigious designers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Unlike any others his designs were inventive, colorful and audacious. These characteristics took other designers and the fashion society by storm.

Born on November 23, 1892, in Saint Petersburg fashion and costume designer Romaine de Tirtoff, also know as Erté (which is the French pronunciation of his initials, R.T.), was one of the most prodigious designers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Unlike any others his designs were inventive, colorful and audacious. These characteristics took other designers and the fashion society by storm.

Erté’s prominent, extended career began at the gentle age of six, through the act of sketching a dress for his mother Natalia Mikhailova. His father, Pietor Ivanovich, an Admiral of the Imperial Fleet, in the end, supported his son’s natural born talent.

Erté left St. Petersburg for France. In 1910–12, he moved to Paris to pursue a career as a designer. He made this decision despite strong objections from his father, who wanted Romain to continue the family tradition and become a naval officer. Romain assumed his pseudonym to avoid disgracing the family. Even as a child, Erte looked effeminate. He wanted to be a ballerina! He hated war passionately, unlike all the men in his bloodline that lived for their military duties. Erte had beauty, not violence, in his heart.

He also enjoyed dressing up - back in the early days. Erté’s theatrical costume designs reflected the spirit of lavish spectacle and indulgence in escapism typical of the era of “decadence.” Interestingly, Erté actually wore his own designs. “I am very fond of masked balls,” he admitted, “and I love dressing myself in costumes created by me and for myself, personally.” A petite, elegant harlequin of a man, no one knew. His presence was unforgettable. Erte liked to intrigue his dinner companions by modeling various Asian robes, wearing a different one for every course served! But even when he dressed fashionably male, he was often mistaken for a woman.

He studied at the Academie Julian and contributed to a Russian fashion magazine called Damsky Mir. Then in 1913, at the age of 21, Erté began designing dresses for Paul Poiret, a famous French couturier. Within that same year Poiret presented some of Erté’s drawings to Lucien Vogel, editor of La Gazette du Bon Ton, France’s most famous fashion magazine during this time period. His first designs for the magazine were published the following year. Erté’s first break into American fashion society was with his cover designs for the chic journal Harper’s Bazaar as a fashion illustrator. Erté contributed his drawing to the journal for 22 years. His first cover for the magazine was published January 1, 1915.

After a few years, Erté began designing sets for plays and musicals. Erté is perhaps best remembered for the gloriously extravagant costumes and stage sets that he designed for the Folies-Bergere in Paris and George White’s Scandals in New York. Erté designed revue after revue: “The Triumphant Courtesan,” “The Queen of Sheba,” “Perfumes”, and “The Treasures of Indochina.”

Like other designers of the Art Deco period, Erté was swept along by the fashion for all things Oriental, by the mania for Egyptian motifs that erupted after Tutankhamen’s tomb was opened in 1922, and by the discovery of African and American Indian art forms. Yet no matter what style or period he exploited, his work had its own fresh integrity.

For one thing, Erté was set apart from other theatre designers of the period by the quality of his finished designs. They are masterpieces of precision, their obsessive attention to detail reminiscent of the Persian miniatures or Russian icons.

In 1925, Louis B. Mayer brought him to Hollywood to design sets and costumes for the silent film Paris. There were many script problems, so Erté was given other assignments to keep him busy. Hence, he designed for such films as Ben - Hur, The Mystic, Time, The Comedian, and Dance Madness.

Coming off of Victorian era clothing, Hollywood would likely never have gotten its reputation for glitz, starlight and glamour if it wasn’t for Erté and the special vision he had of women. Before Erté, women were stuck in Victorian Era clothing: corsets, button up boots, voluminous skirts, high neck collars.

Erté was also in high demand as a fashion designer for a number of Hollywood’s leading ladies, including Lillian Gish and Joan Crawford.

Among the most elaborate of his designing jobs was that done for the show Casanova at the Scala in Berlin, in 1930. His work on this piece was one of the most lavish works Erté had ever done on costumes. His designs lead to the progression of the costumes made especially for music halls.

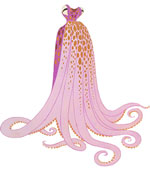

Soon after he worked on a New York show called, The Bottom of the Sea, which gave him the opportunity to create innovative costumes to represent under water creatures. He designed a costume of a lovely pink octopus - a long flowing evening gown that had octopus arms swaying to and fro. Other remarkably designed costumes were those of the capes for the ballet La Mer (The Sea).

It hardly matters if the idea behind a revue was banal or even ridiculous. Whatever the dramatic validity, the effect must have been ravishing.

Another model of the vastness of success within Erté’s fashion career can be seen in his designing outfits and performing pieces for one of the most famous showgirls of her time - Mata Hari.

Erté’s popularity in the fashion world (as opposed to the theatre) waned somewhat after the 1930s. During the remaining years of the forties and fifties Erté remained relatively obscure. Within the sixties he regained his popularity with the Paris Exhibition of his artwork.

In 1988 Erté designed elegant costumes for the Broadway musical Stardust. This would prove to be his last major project. On April 21, 1990, at the age of ninety-eight, Erté died. He was then called the “prince of the music hall” and “a mirror of fashion for 75 years.” (back to top)